Private Variables in ARMA 3 SQF

ianbanks |

Private variables and scopes are pretty simple in ARMA 3 scripting. The

problem is—as it often is—that the documentation isn't very clear.

Confounding matters further, SQF uses dynamic scoping—rather than the more

common and easier to understand conventions of static scoping. A block is any piece of code surrounded by braces, or compiled using the

compile function. You can think of braces as a shortcut for compiling

a string of code. For example, these two snippets of code are practically

identical: The result of both the braced code block and the compile call is to

create a CODE object—the only difference between them is when

exactly the code is compiled. A CODE object—like other objects

such as players, vehicles and strings—may be assigned to variables,

passed to functions, and placed into arrays. The code inside a block isn't executed when the block is created. To make

the code run, the CODE object created by the block needs to be

called, either by using the call or spawn operators, or by

using it in control statements such as if or forEach: When a CODE object begins to run—because you called it or used

it in a control statement—the SQF engine creates a scope. When it

finishes running—either by getting to the end or by exiting early with

exitWith or one of the break commands—the engine automatically

destroys the scope. A scope is created every time a block is called, even if it is the same

block being called multiple times. This is what makes private

variables—which are stored in scopes—private. For example, if you spawn a CODE object that uses a private

variable, twice: The engine creates two independent scopes, which each contain

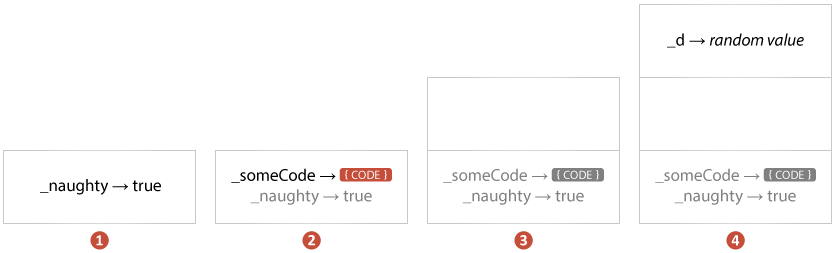

different instances of a variable called _a. Scopes can be stacked on top of each other. When a scope is created, the

engine usually stacks it on top of the current scope, which is the

scope that called the CODE object: As the above example is executed, the scopes look like this: Stacking of scopes is how the engine lets private variables wander out

into other scopes. Consider this code: If scopes didn't stack, the { _value = 0; } code

block would not have access to update the private variable created

in the outer scope. When a scope is destroyed—because the code finished running—it

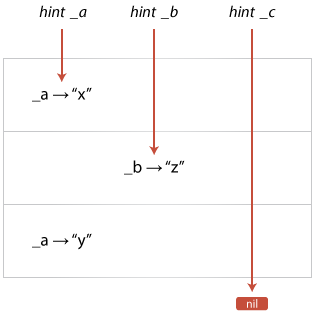

is also taken off the stack of scopes. Scopes are created and stacked based on these rules: When you read a private variable—as in hint _someVariable: The stack of scopes is searched from the current (topmost) scope

downwards until the private variable is found. If it is not found, the

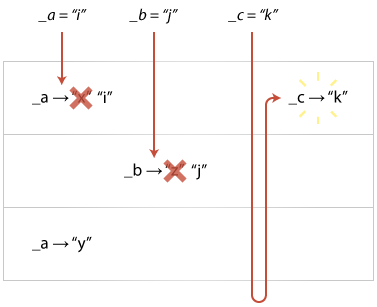

expression result is nil. When you update a private variable—as

in _someVariable = "hello": The stack of scopes is searched from the current (topmost) scope downwards

until the private variable is found. If it is found, it is updated in the

same scope it was found in. If it is not found, one is created in the

current (topmost) scope. Two things can go wrong with this rule. The first is that the current

scope is often not the scope you want your private variable in: The second thing that can go wrong is that you don't always know if a

private variable is already defined in a lower scope. If it is, the

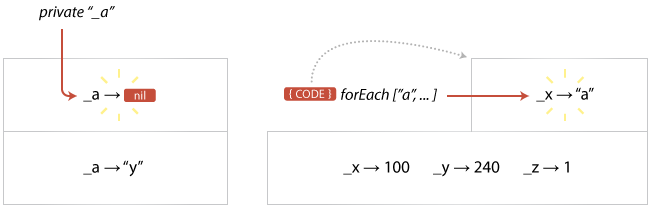

assignment will update it when it probably shouldn't have: To deal with both issues, the following rules exist: Commands like params and forEach work by assigning values

to private variables in a specific scope. The private command

also does this; but it assigns the special nil value to the variable.

You can see this happening with this example: What happens when a private variable exists in more than one scope? The rules stated above for reading and updating private variables explain

this case; the topmost scope that contains the private will be read from or

updated, and the lower scopes containing the same private are ignored; until,

that is, the upper scope is destroyed. At that point the lower private

variable becomes visible again: Assigning nil to a private variable doesn't actually undefine the

variable. nil is a value, just like 1 is a value, and

the rules for assigning it—to private variable at least—are

exactly the same. You can see this with the following example: If _a = nil removed the private variable from the scope, you would

expect the subsequent _a = 3 to be applied to the outer scope. It

isn't—though—and _a continues to be a private variable

within the inner scope. However, global variables are handled differently. If you assign

nil to a global variable, it is considered a special case

and the variable name is removed from the symbol table of the namespace

(which can be verified by making a call to allVariables on

the namespace). One of the consequences of the rules for private variables is that any function

you call can read—and change—every private variable from the bottommost scope of

the first .sqf file executed (with execVM or spawn) all the way up

through the call stack to itself. Take this script for example:

This is true even for compiled functions, like bis_fnc_diagLoop; if the function

reads or writes a private variable without using private first, there is

a risk it will overwrite the variable in some unrelated scope. The only time you might be able to avoid using private is when:

In other words, never. One of the key things to remember about SQF scoping is that

a CODE object has no idea where it was originally created. At first glance,

the following looks like the inner function would have the private

variable _a defined: In SQF—however—it doesn't. The scope that _a

is created in is destroyed once the if block finishes, and

the CODE object assigned to the global inner has no idea

that it was created in that scope. Instead, the only private variables

available to a called CODE object come from the scopes of the

code that called it. This is called dynamic scoping. This isn't the case in other languages. In many other languages, the

equivalent to CODE objects also include references to

local variables that are physically (lexically) close to where they

were created—rather than where they are used. This is called lexical

scoping, and is often preferred because it makes more sense to humans. A common trick (or "idiom") in ARMA 3 scripting is special private

variables, where the engine calls your code with some variables

already defined. For example, forEach does it with _x, and

onMapSingleClick does it with _pos. There are quite a few

in ARMA 3, and for more you can refer to Killzone Kid's comprehensive list of all of them. The same thing is possible from user code, due entirely because of the

rules of SQF's dynamic typing. For example, if you were writing a framework

that allowed the user to hook framework generated events, you could

call the user function with your own special variables: The user code would then expect these private variables to already

exist when it is called:Blocks

if (_naughty) then { player setDamage 1 };

if (_naughty) then (compile "player setDamage 1");

_someCode = { player setDamage 1; };

// The player is always still alive here.

if (1 < 2) then _someCode;

// Now, not so much.

Scopes

_someCode = { private "_a"; _a = random 10; };

[] spawn _someCode;

[] spawn _someCode;

_naughty = true;

_someCode = {

private "_d";

_d = random 1;

player setDamage _d;

_someCode = {

private "_d";

_d = random 1;

player setDamage _d;

};

};

if (_naughty) then

{

// The if resulted in a scope being created for this

// code block; when _someCode is called the engine will

// create another scope and stack it on top of this one:

if (_naughty) then

{

// The if resulted in a scope being created for this

// code block; when _someCode is called the engine will

// create another scope and stack it on top of this one:

call _someCode;

};

call _someCode;

};

private "_value"; _value = random 1;

if (_value < 0.5) then { _value = 0; }

The Rules

if (_someCondition) then

{

_myLocal = 1;

}

else

{

_myLocal = 2;

};

hint str _myLocal; // error; "_myLocal" is not defined.

badFunction =

{

// oops, forgot to use private:

_x = getPos player select 0;

_y = getPos player select 1;

_x + _y

};

{

call badFunction;

hint str _x; // prints the "x" coordinate of the player; eek!

}

forEach [1, 2, 3, 4];

private "_a";

_a = 1;

hint str isNil "_a"; // hints "false"

if (true) then

{

private "_a";

hint str isNil "_a"; // hints "true"

}

private "_a";

_a = 1;

if (true) then

{

private "_a";

_a = 2;

}

hint str _a; // hints "1"

Assigning nil

private "_a";

_a = 1;

if (true) then

{

private "_a";

_a = 2;

_a = nil;

_a = 3;

};

hint str _a; // hints "1"

Always, Without Exception, Use Private

test = { hint str [_a, _b]; };

private "_a";

_a = 1;

call test; // hints [1, any]

private "_b";

_b = 2;

call test; // hints [1, 2]

Lexical Scoping and Dynamic Scoping

if (true)

{

private "_a";

_a = 1;

inner =

{

hint str _a;

};

};

call inner;

A Silver Lining

fwk_fnc_addEventHandler =

{

fwk_eventHandlers pushBack _this;

};

fwk_fnc_invokeNukeDetonationEvent =

{

[] spawn

{

private ["_event", "_radius"];

_event = "nukeDetonation";

_radius = 5000;

{

call _x;

}

forEach fwk_eventHandlers;

}

};

{ hint str [_event, _radius]; } call fwk_fnc_addEventHandler;